Hawaii has been called the extinction capital of the world. Birds, snails and fish native — and, in many cases, unique — to the volcanic-formed archipelago (group of islands) have disappeared throughout the past two centuries with the introduction of invasive species and loss of habitat. Despite this, Stephanie Arellano, an FFA member from Waipahu, on the island of O‘ahu, is using agriscience to bring hope to her community.

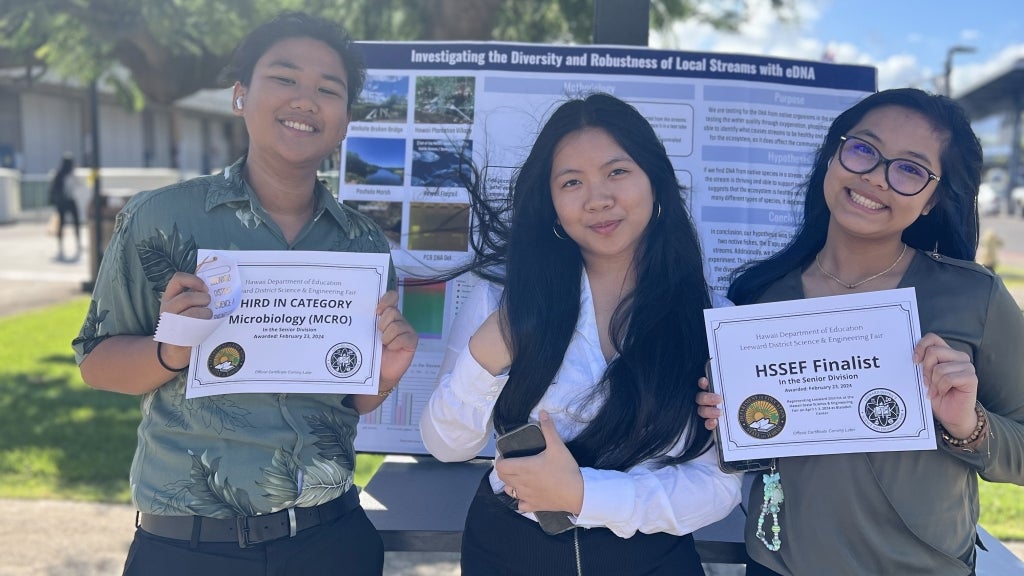

Arellano, a senior in the Natural Resources Academy at Waipahu High School and past Hawaii FFA state officer, is using environmental DNA (eDNA) to show that two native fish species, the Hawaiian flagtail and the ‘o’opu, are still present in local streams that flow into Pearl Harbor.

What Is eDNA?

Environmental DNA is the DNA of an organism found in that organism’s environment. It comes from skin, scales and other materials shed by the organism. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, eDNA is “important for the early detection of invasive species as well as the detection of rare and cryptic species.”

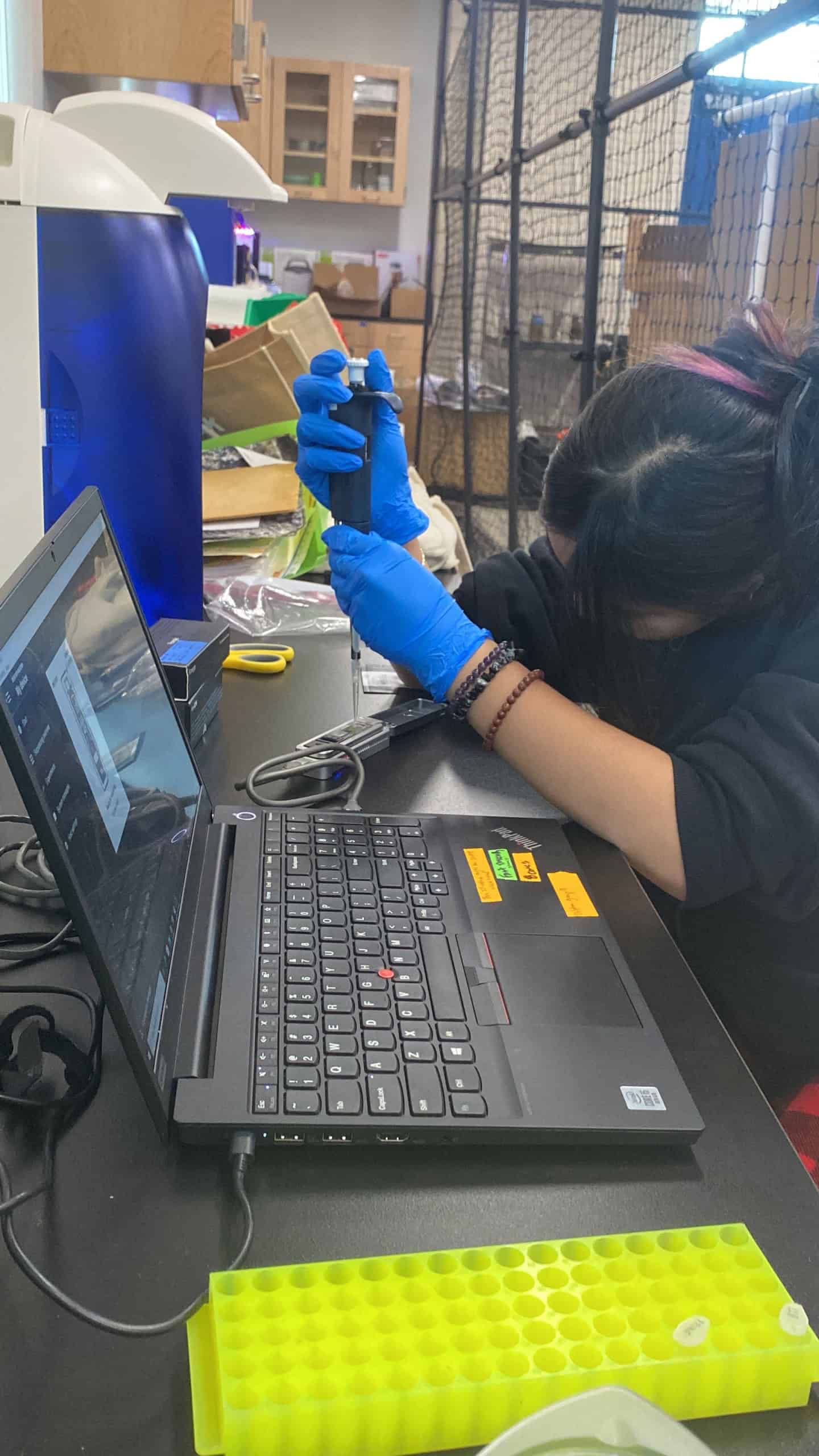

In the search for native fish in Waipahu’s waters, Arellano took stream-water samples from three different sites. She separated debris from the water, then performed water quality tests and sequenced DNA found in fish scales and fecal matter left behind.

DNA sequencing provides “barcodes,” or short sections of DNA. Similar to fingerprints in humans, these are unique to individual species. Even if Arellano never saw a Hawaiian flagtail or ‘o’opu in the waters, she knows, based on DNA barcodes, they are there.

Stephanie Arellano uncovers unique scientific findings through her eDNA research.

“This is important because we have a lot of invasive species, and I want to restore our ‘āina,” says Arellano, referring to the Hawaiian word for “land.” According to the Hawaiian nonprofit organization Trust for Public Land, this word “encompasses the Hawaiian worldview of a reciprocal and familial relationship between people and land.”

“I want to restore Hawaii to its full potential and see more native species we have here for future generations,” Arellano adds.

For the Community

The next step for Arellano is testing for the presence of native fish in more of O‘ahu’s waterways and those beyond, on other Hawaiian islands. She hopes to find additional native species and identify priority areas for restoration using native plants to boost the fish’s habitat so they can better reproduce and thrive.

Waipahu High School already grows native plants in aquaponic systems, one of several different farming systems Arellano has enjoyed learning about through Waipahu FFA. Someday, she hopes to bring high-tech farming solutions to the Philippines, where her family is from, to help Filipinos “grow crops much faster.”

“My passion is to help my community here in Hawaii but also in the Philippines,” Arellano says.

For anyone interested in starting an agriscience research project, her advice is to “just do it.”

“There’s many opportunities,” she says. “It can get you somewhere, honestly, and help you better understand what your passion is.”

Ready to Make Your Own Discoveries?

Conducting and presenting an agriscience research project is a fantastic way for you to explore your interests, gain hands-on experience and discover potential careers. To learn more, click here.