In an important step to ensure FFA is a place where all people can prepare for leadership and career success, the North Carolina School for the Deaf became the third FFA chapter in the nation for members who are deaf and hard of hearing.

Although the North Carolina School for the Deaf was established in 1894 and was once the site of a productive farm with massive vegetable gardens and a herd of dairy cattle, lessons about agriculture were not part of the curriculum.

“No one has ever been here to teach students about food and agriculture,” says Reid Ledbetter, the agricultural education teacher and FFA advisor at the North Carolina School for the Deaf. “Given the history of the land, it made sense to have an agricultural education program here.”

In 2018, as part of an effort to ramp up its career and technical education program, the North Carolina School for the Deaf launched an agricultural education program for students in middle and high schools. Ledbetter chartered the first FFA chapter in school history, which also became just the third school for the deaf in the nation to have an FFA chapter.

“FFA is about leadership, hands-on learning and STEM education,” Ledbetter says. “If we wanted to have a complete ag ed program, FFA needed to be part of it.”

Rebecca Carson

Students Dig In

The North Carolina School for the Deaf FFA Chapter accomplished a lot in its first season. The 106-acre grounds sprouted a new garden and a high-tunnel greenhouse that produced fruits and vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, potatoes, sweet potatoes, cabbage and blueberries. Younger students grew snow peas in a square bale garden.

Students are responsible for all aspects of production – from planting seeds to tending plants to harvesting. The gardens do not grow enough fresh fruits and vegetables to serve all of the students living on campus, so the produce is distributed to families of students through the onsite food bank. Students take bags of fresh food home on weekends. Growing food on the campus is about more than feeding families in need, Ledbetter says.

“Students learn best by getting out there and trying new things, so we try to incorporate as many hands-on activities as we can,” he says. “Most of the students at our school are from cities or urban areas and have never had these opportunities before.”

High school senior Rebecca Carson spent a lot of time among the cows, pigs, goats, horses, chickens and rabbits at her grandparents’ farm, but she appreciated classes on plant and animal sciences, and the chance to put those lessons into action on the school farm.

“My friends encouraged me to join FFA because it was fun learning outside the classroom,” she says through a sign language interpreter.

Carson developed an immediate affinity for agricultural education and became the vice president of the North Carolina School for the Deaf FFA Chapter. Member KaZoua Vue, 18, has a small flock of chickens at home, and she loves working with the chicks at the North Carolina School for the Deaf. The agricultural education program purchased eight chickens this spring and plans to continue adding to the flock. When the hens start laying, the eggs will be distributed through the school food bank.

“I like weighing the chickens and watching them change each week,” Vue says.

KaZoua Vue

Too Good to Pass Up

The FFA chapter is growing as fast as the chicks.

The North Carolina School for the Deaf serves deaf and hard of hearing students from 43 North Carolina counties. The FFA chapter, which started with just 10 students, has almost doubled in size and earned an award at the state FFA convention for the biggest increase in membership.

Two students attended the North Carolina state FFA convention to accept the award.

For students such as high school senior and chapter president George Righter, 18, the chance to get their hands dirty while connecting with the source of their foods was too good to pass up.

“My first year in agriculture science applications class was my first real experience in agriculture,” he says through a sign language interpreter. “It’s important for all students to know where their food comes from. I like working outside planting the potatoes, and I have an interest in teaching and STEM education.”

All of the FFA members and agricultural education students are excited to learn more about agriculture and participate in activities such as growing vegetables, raising chickens, growing gourds, and making birdhouses and grapevine wreaths, Ledbetter says.

Students learned about mechanics in the agriculture science applications class, and they had the chance to see all of the latest high-tech farm equipment during field trips to the Southern Farm Show in 2018 and 2019. “We try to do all of the things other chapters would do,” Ledbetter says. “We participate in local, regional and state activities and plan to attend the next National FFA Convention & Expo in Indianapolis.”

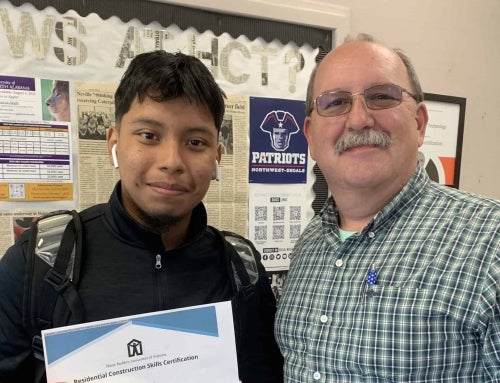

George Righter

Community Assistance

Ledbetter has a long history in agriculture and education. He participated in FFA in high school and worked on the dairy research farm while studying agricultural education and animal science at North Carolina State University. He is also a first-generation dairy farmer, and he taught agricultural education in Iredell and Scotland counties. He had no background, however, in sign language when he accepted the position at the North Carolina School for the Deaf.

In his first year in the classroom, Ledbetter taught with the help of an interpreter. He spent the last two years taking American Sign Language classes and can now communicate with students in ASL.

In addition to communicating with students, Ledbetter has spread the word about the new agricultural education program and FFA chapter in the local community, and he’s thrilled with the amount of support the school has received.

The North Carolina Tobacco Trust Fund and Carolina Farm Credit provided grants to help the school purchase a hoop house, garden tools and FFA jackets. The Burke County Beekeepers Association donated a beehive and bees. The Burke County Master Gardeners paid the FFA dues for the fledgling chapter. Farm Bureau donated copies of its 2019 Book of the Year for students.

“The community sees it as a really great opportunity to connect with the school and the students,” Ledbetter says. “There is a lot of excitement about the program. We’re small but growing. I’m the ag teacher so I might be biased, but there is no other program this school could start that would give these students such amazing opportunities.”

A Movement for Deaf Members

The North Carolina School for the Deaf was the third school for deaf and hard of hearing students to charter an FFA chapter. So which were the first two?

The agricultural education program and FFA chapter at the West Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind in Romney, W.Va., dates back to the 1960s. Members learn welding, learn how to hatch chickens and tend the flock, work in the greenhouse and more. During an annual plant sale each spring, students sell the annuals, vegetables and hanging baskets they grew in the greenhouse.

“In its heyday, the school had a fully operational farm on campus with a bakery, dairy, processing facility and greenhouses,” says West Virginia School for the Deaf agricultural education teacher and FFA advisor Amanda Whitacre. “Our students still love to do things with their hands and grow things. It provides a sense of accomplishment.”

The Kentucky School for the Deaf in Danville, Ky., started its agricultural education program and FFA chapter in 2009, turning part of its 23-acre campus into an outdoor classroom for students interested in getting hands-on education in agriscience.

Photography by Tyler Smith

JOIN FFA CHAPTERS ACROSS THE COUNTRY IN OUR CHALLENGE TO COMPLETE 930,000 VOLUNTEER HOURS BY THE 93RD NATIONAL FFA CONVENTION & EXPO.

#FFAChallengeAccepted

August 2020 Winners

Taylor County FFA

Kentucky

Carlisle County FFA

Kentucky