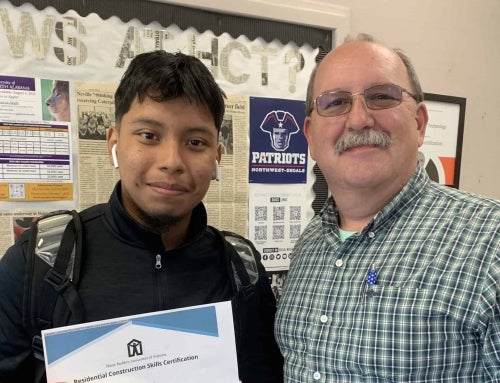

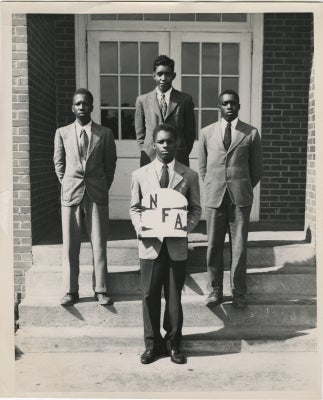

Four members of the North Carolina Association of New Farmers of America (NFA) attend state convention (c. 1950).

“I keep records of receipts and disbursements just as Washington kept his accounts — carefully and accurately. I encourage thrift among the members and strive to build up our financial standings through savings and investments. Booker T. Washington was better able to serve his countrymen and posterity, because he was financially independent.”

While the majority of FFA members can recite the first two sentences of this quote from memory, the third is less familiar. These words have not been spoken in an official agricultural education meeting since the New Farmers of America (NFA) and the Future Farmers of America (now National FFA Organization) became one organization more than 50 years ago.

While labeled a merger in 1965, the NFA was basically absorbed by FFA. At the time, both organizations were independently successful in honing leadership skills and providing professional development opportunities for young men in agriculture. Since combining, however, the number of Black Americans who benefit from activities in FFA and agricultural education has decreased drastically. Many of the traditions, history and culture of Black agricultural education have been erased or forgotten.

With recent research by Antoine Alston, Ph.D., professor and associate dean at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, and Dexter Wakefield, Ph.D., professor and associate dean of academic programs at Alcorn State University, more is known about the experiences of former NFA members.

“If you think about the age of a former NFA member or even NFA teachers today, they would be more than 75 to 80 years old,” says Alston. “Our time to learn from these early, Black agricultural leaders is running out. If we don’t capture their experiences and their memories now, it may soon be lost to history.”

Understand the History

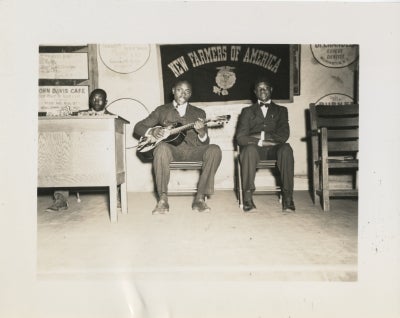

Entertainment was provided during most chapter, state and national NFA meetings.

The roots of NFA can be traced back more than 140 years to Booker T. Washington, an influential educator, author and civil rights leader.

In 1880, Washington, the son of former slaves and an advocate for black progress through education and entrepreneurship, established an agricultural class for Black boys in his one-room school in Tuskegee, Ala. Beginning in 1896, the segregation of races in educational establishments was instituted under the “separate but equal” doctrine created by Plessy v. Ferguson, a U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court decided that racial segregation laws were constitutional as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality. It would remain in practice by the United States for the next 70 years, and ultimately led to the creation of similar but separate organizations like NFA and FFA.

Later, passage of the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 — barely 50 years removed from the end of slavery — provided funding to states for vocational and agricultural education. Dr. H.O. Sargent was soon appointed as the first federal agent of vocational agricultural education for special groups, which included Black, Hispanic and Native American citizens. He was widely accepted by Black agricultural educators, and under his leadership, Black agricultural education expanded and many Black teacher-trainers were awarded fellowships for graduate studies.

Understand the Journey

In 1927, Sargent teamed up with G.W. Owens, a teacher- trainer at Virginia State College, to draft the first constitution and bylaws for New Farmers of Virginia, an organization for Black agriculture students. That same year, 400 New Farmers of Virginia members from 18 chapters held a state rally to create more interest in the vocation of farming, encourage cooperative effort among agricultural students and develop rural leadership.

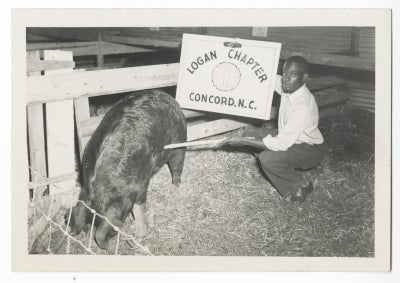

An NFA member and member of the Logan Boar Association from Concord, N.C., shows his boar as a part of his swine project in 1941.

From 1927 to 1935, plans for the national NFA organization took shape and it was officially formed Aug. 4, 1935, at Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Ala. From then on, an emblem comprising a plow, owl, rising sun, open boll of cotton, American eagle and the words “NFA” and “Vocational Agriculture” graced the black-and-gold jackets of NFA members across the country. Active members earned degrees as the Farm Hand, Improved Farmer, Modern Farmer and Superior Farmer, and they would compete in events such as dairy farming, farm electrification and public speaking. A quartet contest was held to develop a greater appreciation for music, including traditional Black spirituals.

NFA operated autonomously from its inception in 1935 until 1941. During this time, NFA grew to consist of 1,004 chapters in 12 states and more than 50,000 members. In 1941, the U.S. Department of Education — which didn’t employ a single Black person to represent NFA — brought NFA under its own authority, removing authority from the NFA leaders of that time. NFA leaders recognized the need to secure leadership positions in education departments to support their interests at the local, state and national levels. Over the next two decades, NFA leaders made repeated attempts to gain representation.

Meanwhile, momentum for “separate but equal” legislation began to slow. In addition to other court cases, in 1954, the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” and ordered an end to school segregation. Individual states enacted desegregation legislation and, as a result, five of the 17 state NFA associations in existence at the time merged with their state FFA associations.

NFA National Board of Trustees in 1956

Understand the Losses

While desegregation was a milestone, the way in which it was carried out ended up hurting the Black community. As schools began to merge, the resulting agriculture programs couldn’t support two agriculture teachers; more often than not, Black teachers lost their jobs to white teachers. In other cases, Black teachers were demoted from being a vocational agriculture teacher to a lower category, leading to smaller salaries and reduced opportunities. Leadership positions were largely given to white individuals, leaving Black students and teachers unrepresented.

In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. While the implications of this act would desegregate all schools and school-based activities, it also led, through a merger with FFA, to the end of NFA and the culture built around it. The merger was ultimately one-sided, as NFA gave up its name, charter, constitution, bylaws, awards, emblem, jacket, Creed, flag, banner, colors, financial assets and adult leadership. Meanwhile, FFA gave up nothing — not even a single seat on its board of directors.

“The events around the NFA/FFA merger were a federal mandate from the U.S. government,” says Wakefield. “There was a feeling that this merger was inevitable and not such a bad idea, but there was an expectation that Black students would be provided equal opportunities in all positions and activities. It did not happen.”

These long-lasting impacts are still felt today. In 1965, more than 52,000 young men were members of NFA. Today, just 36,000 FFA members identify as Black, which accounts for only 5% of membership.

An NFA member gathers eggs as part of his poultry supervised farming practice.

But Alston says not all of NFA disappeared.

“While there was significant loss, there are a lot of NFA activities that still exist as a part of FFA today,” says Alston. “The challenge has been around access. It’s all about resources when it comes to being an effective organization. Decades ago, resources were a barrier when agricultural education membership [costs] went from 5¢ in the NFA to 50¢ in FFA. Back then, it was typically not feasible for students who did not have financial resources to receive an award in the FFA.”

In his research, Alston heard from one NFA advisor who said, “We lost a lot; lost some great opportunities. [We] should have kept the vision of NFA, and we would be better off. We lost our camp; lost employment. We lost so much, [which] still impacts [us] today.”

The Black community began experiencing a decline in representation in agriculture, as some Black teachers and leaders were pushed from their positions. Black students, in turn, lacked role models in the field; those students who wanted to pursue agricultural careers were encouraged to choose other pathways.

“Today, even students who have [financial] resources [to pursue careers in agriculture] are being told to choose another career pathway,” says Alston.

Wakefield adds, “Underrepresented students are traditionally unaware of the potential of success in the agriculture field of study” because they’re encouraged to pursue other careers, instead.

Understand What Is Possible

“We must address the tough topics of our past to help our organization create an accessible and inclusive future,” says James Woodard, National FFA Advisor and chair of the National FFA Board of Directors. “FFA is made up of more than 700,000 members, each with their own unique history, heritage, interests and vision for the future. We honor and respect the differences among us that make us stronger.”

NFA members show beef cattle at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (c. 1950).

Learning what happened in 1965 may inspire members to take action and ensure the NFA culture is not lost. What could this look like? Movements start at the grassroots level with members and chapters. Perhaps members can initiate a scavenger hunt through the NFA archives. Or chapters can invite community members who were students during segregation to share their experiences or become an honorary chapter member. Maybe members will find inspiration in the former NFA talent programs and host a quartet competition. Chapters may look to supplement copies of the Official FFA Manual with additional historical material on NFA to ensure the past is not forgotten. Start small now, then think bigger.

Regardless of the actions members are inspired to take or the emotions processed, recognition of the NFA perspective is a step to reevaluate a decades-old absorption and turn it into a true merger — making FFA an organization for all.

Understand Our Potential

For one FFA member in Tennessee, a gap in a history lesson led to a drastic shift in the way NFA history is taught at his school.

During a class lesson, Malachi Johnson raised his hand to challenge his class on why there wasn’t more information regarding the history of the New Farmers of America (NFA). The question went unanswered, and members of the Scotts Hill FFA Chapter have made it their mission to research NFA and build a more robust history lesson. Throughout the process of finding the hidden history of this organization, the chapter made a rare discovery — the jacket of a former NFA member, which now hangs proudly in their classroom.

Today, Scotts Hill FFA has a Human Resources Committee; members of the committee are conducting interviews with original members of NFA chapters.

These interviews will be compiled into a documentary, allowing the voice of former NFA members to be heard by all. Follow along with these FFA members as they journey through NFA history on their chapter Facebook page.

This year, Okmulgee FFA is celebrating its 70th anniversary. The chapter was founded as an NFA chapter at Dunbar High School in Okmulgee, Okla. in 1951. In honor of the anniversary, chapter officer LeAundre Delonia sat down with former NFA members Leman Lewis and Charles Williams to talk about their years in NFA . Watch the video here.

PRESERVING THE PAST

The National FFA Organization is helping to fund the NFA Archives project in 2022 to ensure these important perspectives are not lost.

Antoine Alston, Ph.D, and Dexter Wakefield, Ph.D, are also creating an NFA pictorial to document the history of NFA through photos.