Each year at the National FFA Convention & Expo, four FFA members are honored with American Star Awards for outstanding accomplishments in FFA and agricultural education.

The American Star Awards, including American Star Farmer, American Star in Agribusiness, American Star in Agricultural Placement and American Star in Agriscience, are presented to FFA members who demonstrate outstanding agricultural skills and competencies through completion of an SAE. A required activity in FFA, an SAE allows students to learn by doing, by either owning or operating an agricultural business, working or serving an internship at an agriculture-based business or conducting an agriculture-based scientific experiment and reporting results.

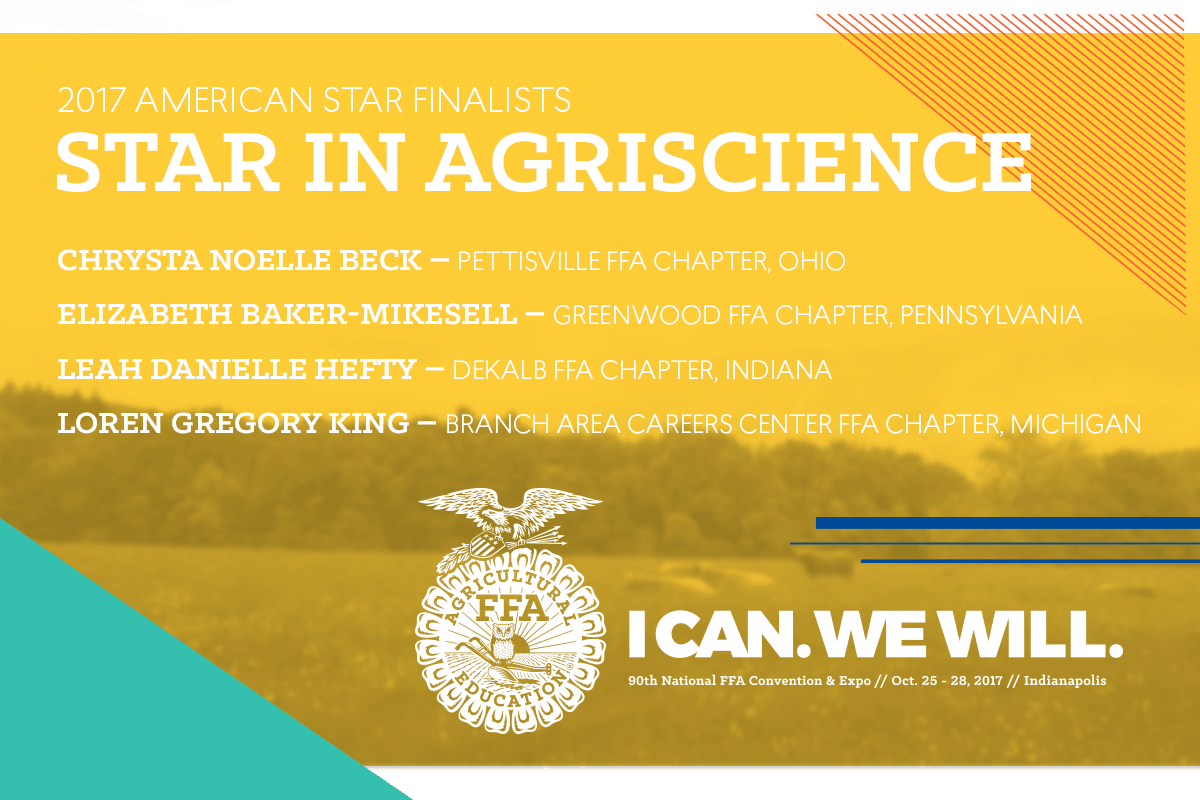

Here are the 2017 finalists for American Star in Agriscience:

Libby Baker-Mikesell (Pennsylvania)

Libby Baker-Mikesell competed in her first science fair as a second-grader. Her goal at the time was clearly defined: find a problem and then create a solution. The Port Royal, Penn., resident met the challenge and took that direction to heart, but she didn’t stop there. As Baker-Mikesell grew older, she continued seeking processes and situations in need of improvement on her family’s farm.

As an FFA member in high school, she combined her supervised agricultural experience (SAE) in beef production with an agriscience research SAE, which focused on the dilemma of having limited space for both manure storage and compost on her farm. “I composted cattle manure with different carbon sources to see which would be most effective,” Baker-Mikesell says. “That was spread over our land. The next year I grew grasses with the same composts to see how effective the previous year’s research was, and then I just put a practical application to that.”

Pleased with the success of that experiment, she expanded her research to include agricultural findings that would have regional impact and value as well.

With her family farm located in the middle of the impaired Chesapeake Bay watershed, Baker-Mikesell knew this was an area she wanted to explore. So she grew different short-seasonable crops, such as buckwheat, sorghum-sudan grass and oats, to determine which ones would decrease the amount of phosphorous in the soil naturally (without additives). She discovered that sorghum-sudan grass had the highest phosphorous uptake, followed by oats.

“I’m proud that I’ve developed some of the best management practices that farmers across the region can use to hopefully increase the health of the bay,” Baker-Mikesell says.

Her research has earned her top honors of being named a 2017 Star Finalist in Agriscience.

She challenges other FFA members who are looking for ideas for an agriscience project to think of where they live, a question they might have and a way to answer it. “Whether they live somewhere else and have a passion for food science or agricultural technology, there’s agriscience,” Baker-Mikesell says. “There are opportunities for pretty much everyone.”

Baker-Mikesell plans to start a dual major next year in agricultural education and plant sciences. “I’m taking my love of agriculture and my experience in research, and I’m finding a passion for plant and environmental sciences,” she says. “I’d like to teach the next generation about the importance of agriculture and conservation and how all of that can be used.”

Baker-Mikesell is the daughter of Robert and MeeCee. She is a member of the Greenwood FFA Chapter, led by advisors Krista Pontius and Michael Clark

Chrysta Beck (Ohio)

Since third grade, Chrysta Beck of Archbold, Ohio, has raised broilers and layers to sell meat and egg products to local customers. As she got older and joined FFA, she developed a supervised agricultural experience (SAE) that would look into the health of poultry. But what started as research to assist her with personal production goals soon developed into a project with a vastly larger scope. It focused on U.S. and global poultry production and welfare.

Beck’s work began when she was in ninth grade and started looking closely into broiler production factors and exactly how the birds grew. She also learned how to determine meat quality. By her senior year, Beck was investigating alternative methods for replacing antibiotics.

“I was looking into the gut health of the chick,” Beck says. “I was looking into the microbiology of chickens and doing probiotic research.”

In her lab trials, Beck has been testing different types of bacteria to determine their viability. Through in ovo technology, a probiotic is injected into a developing embryo prior to it having any contact with harmful bacteria in the external environment. This allows the chicken’s gut to contain beneficial bacteria when it hatches, rather than being subjected to harmful bacteria after hatching.

“In theory, the harmful bacteria doesn’t have the opportunity to inhabit the broilers’ gastrointestinal tract, since a beneficial bacteria is already there,” Beck explains. “I want to help the bird from Day One to have an extra boost.”

Beck says that from her work over the past six years she is discovering the future of the poultry industry and conducting studies she has only dreamed of. “It’s important that we have this research so we can understand the future of this industry,” she adds.

This research has earned her top honors as she has been named a 2017 American Star finalist in Agriscience.

Beck is currently studying at Mississippi State University and plans to return to the industry as a poultry vet. She credits her advisor and FFA Alumni for helping her and inspiring her interest. “FFA helped me with leadership skills and public speaking,” Beck says. “It was very beneficial.”

For those looking to pursue an SAE, she offers the following advice: “Do not be afraid to try something different. Do not be afraid to stand out, even though it may be a little uncomfortable at the time.”

Beck is the daughter of Beth Ann and David. She is a member of the Pettisville FFA Chapter, led by advisor John Poulson.

Leah Hefty (Indiana)

Leah Hefty enjoyed taking her animals to a local nursing home to offer residents the joy of visiting with her. But the cost of hay to feed her animals was always a concern. Entertaining as they were to watch and pet, the animals needed to eat. But instead of looking at their food expense as an obstacle, the Auburn, Ind., resident saw it as an opportunity to find a solution.

She soon began working with her FFA advisor and created a supervised agriculture experience (SAE) that challenged her to find a more cost-effective feed alternative to hay.

Her research has earned her top honors of being named a 2017 Star Finalist in Agriscience.

An idea came to her when she realized her uncle had a problem with an overabundance of algae growing in his pond. “He was going to kill it off, but I saw potential,” Hefty says. “I figured there has to be something that you can do with this algae to make it useful.”

So she collected some of the algae and let it dry. Then she carefully measured and mixed different ratios of algae with hay to feed her goats. She wanted to see if it was palatable as well as nutritious for them. Through her project she proved that the algae was, in fact, palatable to the goats, and verified that they were getting all of their nutritional needs met.

“Algae seems to grow anywhere, which is good for a project like this,” Hefty says, “But it’s bad when you don’t want algae around.” Hefty points out that with hay, you have to wait for it to grow a certain height before cutting, baling and storing it. But with algae, she has a steady supply.

“You harvest it, and as need be, let it dry,” she says. “Algae can be added on an as-needed basis.” (It takes less than 24 hours to dry, if it is a thin layer.)

She says FFA and her agricultural education classes taught her the value of persistence. “Once you start a project, there’s always going to be little bumps in the road, and there’s always going to be little events, especially when dealing with plants and animals.”

Hefty takes great pride in her projects and the fact that they can be implemented on a community-wide scale. “I never did a project that I thought would only benefit me or just a small group of people,” Hefty says. “I always made sure that my projects could benefit my community as a whole, especially those who don’t completely understand agriculture.”

Hefty is the daughter of Danielle and Michah. She is a member of the DeKalb FFA Chapter, led by advisor Matt Dice.

Loren King (Michigan)

Raised on a farm that embraces GPS guided tractors and satellite maps, early on Loren King developed a penchant for problem-solving involving technology.

Throughout the past few years, King has had opportunities to learn how technology is shaping the landscape of agriculture.

The Branch Areas Career Center FFA member developed a supervised agricultural experience (SAE) that focused on emerging agricultural technology. King’s ingenuity has earned him top honors as being named a 2017 finalist for American Star in Agriscience.

The Burr Oak, Mich., resident remembers an evening when his father and grandfather were monitoring their fields because of runoff issues, and they used Gators to go and test. King thought there should be an easier way. Later, when he was reading an issue of Popular Science, the idea came to him: They should use a drone.

After reading about drones, he thought about the possibility of using one to help with the testing. A year later, King put his research to the test and built a drone.

“It was completely custom,” King says. “I ordered all the parts, soldered everything and did all the programming.” He then hooked up two soil sensors, one to view the pH and the other one to view moisture content, sunlight amount, and temperature.

He began testing in several different fields with different soil types. Then he adjusted his drone to raise and lower its sensors to protect them from possible damage on impact.

“My motivation for doing this stems from watching how my family has previously solved things,” King says. “I was looking to apply this as something that could grow and become even greater than what I was able to do with it.”

His drone is designed to fly and land. Its two sensors then push directly into the soil and through Wi-Fi, data is sent back to the phone.

King admits the process wasn’t without challenges. He notes it took as many as 25 attempts to get the drone running the first time. as it was self-built. “I really had to grow through that process,” King said. “The people around me would just encourage me the whole time in the class.”

This research, King notes, is important, because we’re moving to a future where everything has to be more efficient. “If you’re talking environmentally, there’s going to be requirements coming out soon. So being able to show real-time data, by just sending out your drone, can show real, physical evidence of how we care for our farms.”

While King remains undecided on his future, he thinks his drone will play a part in some startup. “I definitely want to turn this into some type of business to get the technology out there so that others can use it,” he says.

King is the son of Angie and Bart. He is a member of the Branch Areas Career Center FFA Chapter, led by advisors Carrie Preston and Alison Bassage.