This post originally appeared on the blog of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

High school can be a challenging time for teens. Much as they do today, young men and women throughout the 20th century wrestled with identity, education, and social status during their teenage years. For young women in the 20th century, changes in the way people thought about gender and equality greatly impacted their experience. Documenting those changes for teens is an important aspect of telling a larger story about the changing roles of women in the 20th century. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History has found an interesting way to tell that story through its agricultural collection.

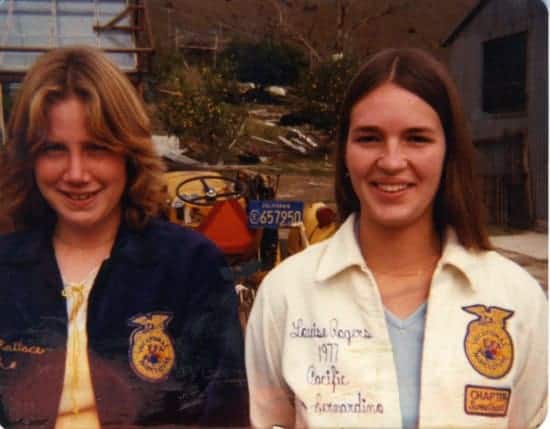

The story of the Future Farmers of America (FFA) jacket once worn by Louise Rogers (now Mary Louise Reynnells) explores teenage life, high school, and how a national organization changed with the times. The museum collected the jacket because it symbolizes a large youth membership group—the National FFA Organization—and because its distinctive white color evokes decades of debate over women’s role in society.

As seen in this 1928 photo from the founding meeting of the Future Farmers of America, membership was male. Two years later, the group formally excluded membership of young women.

The Future Farmers of America, founded in 1928, is a national school-based organization that offers students in grades seven through 12 structure and purpose. In 1998 the group changed its name to the National FFA Organization, or FFA for short. More than just agricultural learning, participation in the FFA gives teens independence and membership in a supportive group. Being in the FFA is, as alumna Gina Whiteman describes, an “opportunity to grow as individuals.”

Gina Gorrell (now Gina Whiteman), Judson, Texas, 1990s. Competing in the FFA builds important life skills. “The animal projects require discipline and responsibility,” Whiteman said.

In the early 1900’s, as Americans began moving off farms and into cities, many people began to worry about a rural brain drain. A number of remedial actions were proposed in what became known broadly as the Country Life Movement. Virginia State Supervisor of Agricultural Education Walter S. Newman and staff members at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute Agricultural Education Department collaborated to form an organization to instill pride and promote leadership skills in youth interested in pursuing farm work. Others agreed, and in 1928 the Future Farmers of America was created. However a dispute quickly cropped up about who could join and fully participate. Two years later, at the 1930 FFA convention, the delegates clarified membership by voting to exclude young women.

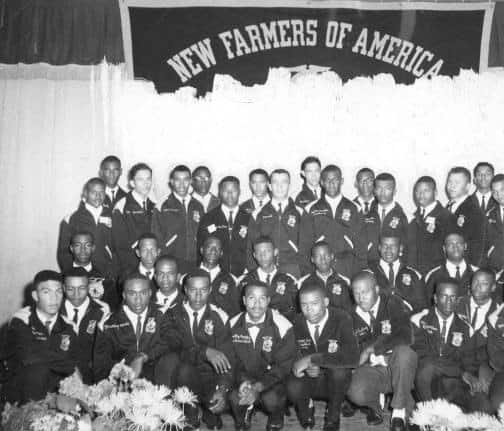

Both gender and race relations impacted the FFA. Jim Crow laws kept black students out of vocational agriculture classes in some school districts and thus the FFA. A parallel organization for African Americans, the New Farmers of America (NFA), was founded in 1935. Growing to a membership of 58,000 in 18 states, the NFA merged with the FFA in 1965. The Smithsonian is currently searching for a black corduroy NFA jacket to document this important chapter of American history. If you have one you’d like to offer to donate to the museum, send us an email describing the jacket and sharing its story to agheritage@si.edu.

But as happens with many issues, the FFA struggled with tension between state views and national perspectives. Some local FFA chapters allowed young women to join and participate in regional and state meetings and competitions. In fact, some women even attended FFA camps under the guise, as one current-day official described with a wink, of being an instructor’s daughter or niece. In 1935 the Massachusetts FFA protested that women should be able to fully participate. However the national organization stood fast in denying membership to young women.

Nevertheless, some women found ways to bend and break the rules. After all, the FFA grew out of school-based agricultural vocational education and, in many states, it was illegal for publicly funded programs to restrict membership based on race, religion, color, or sex. For many young women attending rural high school, pursuing agricultural education was a natural choice, as women have always shared responsibility in farming and ranching. But perhaps of greater importance was the leadership training that the FFA offered. Personal development, public speaking, and community action are key FFA goals, and those activities help members prepare for management positions in all walks of adult life.

In 1933 the Future Farmers of America chapter of Fredericktown, Ohio, modeled its blue corduroy jackets. The national convention delegates enthusiastically voted to make it an organization standard.

But back to the jacket. The FFA adopted a blue corduroy jacket as the member uniform in 1933 and the rules demanded that they be worn for most leadership activities (rough clothes could be used when cleaning out the barn). The jacket was a badge of honor and a uniform of distinction that women, by membership edict, could not wear. Even borrowing a jacket was not possible. Unlike athletic letter jackets, FFA jackets were not supposed to be shared with a girlfriend. As LaDonna Lee, ag consultant and partner in Mile High Ranch, recollected, “whether it was a rule or custom, a boy was said to be kicked out of the chapter if he allowed his girlfriend to wear his jacket.”

Louise Rogers’ white FFA jacket (pictured left) is remarkably different than Jesse Godbold’s standard blue corduroy jacket.

But there was a loophole to the FFA membership rules. From 1949 to 1969 a young woman could, in fact, qualify for a coveted FFA jacket by becoming a chapter’s “Sweetheart,” or social ambassador. With this honor they could then sport an FFA corduroy jacket (it switched from rayon to corduroy around 1960). Not quite equal, the FFA Sweethearts wore white corduroy jackets instead of the standard blue.

As we discuss in American Enterprise, where we display FFA member jackets, the 1960s was a time of empowerment and change for many women. Muriel Siebert became the first woman to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, Caroline Jones broke both gender and racial barriers in advertising, and journalist Gloria Steinem wrote articles that helped awaken a new feminist consciousness across America.

But the FFA held fast to tradition and voted against extending membership to young women in 1967 and 1968. Finally in 1969, with court action likely, the national organization came of age and admitted women as full-fledged members. Soon after, Anita Decker and Patricia Krowicki became the first two female delegates to the 1970 National Convention.

In 1976 Julie Smiley became the first female national officer and in 1982 Jan Eberly was elected the first female National FFA President. Perhaps the final barrier was broken in 2002 when Karlene Lindow of Chili, Wisconsin, became the first young woman ever to be named Star Farmer—the FFA’s highest agricultural award.

Peter Liebhold is a co-curator of the American Enterprise exhibition and a curator in the Work and Industry Division at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.